The following article appeared at Townhall.com on July 10, 2019.

General Douglas MacArthur once said, “The soldier above all others prays for peace, for it is the soldier who must suffer and bear the deepest wounds and scars of war.”

Having served in the Army in combat as a special operations physician, I have seen soldiers suffer the scars of war, both visible and invisible. Tragically, in the past two years, invisible scars of war are taking their toll as the rates of active-duty military suicides have increased dramatically. Just as we prepare our fighting forces physically and with proper equipment, it is our duty to ensure warriors and veterans are mentally, emotionally, and especially, spiritually prepared for war.

For some who hear the phrase “spiritually prepared for war,” the gut reaction to mixing faith and killing in war is repulsive. That gut reaction comes from the same conscience that creates and sustains what psychiatrists call a moral injury.

In our Judeo-Christian culture, the principles of “Thou shalt not kill” are embedded in most of our psyches. We shame those who practice violence. In our society, the bully is appropriately condemned. Then a young man or woman joins the Army or the Marine Corps and is taught to kill. Killing becomes the profession and “violence of action” the means of survival. If you’re horrified watching the first few minutes of Saving Private Ryan, that feeling is amplified ten times when the blood is real, and it’s your best friend’s.

From my experience, those who go to war and return experience one or two moral struggles. Either they’ve taken a life, or they’ve survived when a good friend did not. The struggle to accept that you killed someone, and what is called “survivor guilt," become two primary drivers of moral injury. They haunt the veteran. Those who do not overcome the moral wounds self-medicate. Or, all too often, those afflicted end their lives.

These moral injuries happen to soldiers and Marines regardless of faith or religious background. But how the soldier or Marine responds to moral injury varies. When it comes to suicide, the data is undeniably clear. Religious people appear to be at less risk for suicide.

One Nurse’s Health Study surveyed nearly 90,000 women for over a decade. This study found that those women with regular religious attendance have a five-fold lower risk of suicide compared to women who did not attend religious services. This also seems to correlate to veteran suicide. In a study, Dr. Kopacz with the VA observed that veterans who attempt suicide self-rated their spiritual health in a worse category than veterans without suicide ideation.

Another study in March of this year concluded that “negative spiritual coping” was often associated with an increase in mental health diagnoses and symptom severity, while “positive spiritual coping” had a healing effect. Even the data the U.S. Army presented to the Oversight Committee on May 8th, 2019 reveals much. Fifty-seven percent of the active-duty Army soldiers who committed suicide in 2018 had no religious leaning, even though non-religious soldiers compose roughly only 33% of the Army. Non-religious soldiers are killing themselves at a faster rate than religious soldiers.

My belief, supported by the correlation seen in the data, is that religion helps men and women cope with the pains of war. After all, the three most popular monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – all teach how to cope with both guilts.

Now, not every soldier is religious. And we should never force religion on anyone. But studies that ask whether soldiers are religious or not reveal the U.S. Army essentially reflects society. Two-thirds say they believe in some religion. Those who are religious should be able to have access to resources. When a soldier deploys, or is on training, he or she cannot pack their church or synagogue and put it in their ruck sack. We need an engaged clergy in the U.S. Military – it will save lives.

Yet there seems to be an assault on religion in the military. Chaplains report that they cannot approach soldiers about this issue. Chaplains are being disciplined because they refuse to operate outside their specific beliefs despite the fact that the NDAA specifically says Commanders cannot force a chaplain to do something in violation to his or her beliefs. Commanders are not allowed to pray at certain ceremonies, and religion itself is ridiculed. The associations that represent chaplains have all voiced concerns that their members cannot address the spiritual needs of warriors, despite the data which shows it can save lives.

Without the proper spiritual counseling, at least to those who consider themselves spiritual, we are sending warriors into battle unprepared for the emotional challenges.

Every commander can tell us how well their equipment is ready to deploy. Things like marksmanship and training on various maneuver tasks are all measured. Yet hardly any could measure the spiritual readiness of those soldiers who self-identify as spiritual or religious—because to do so would upset the politically-correct anti-religion crowd despite the fact that we may be able to save lives.

It is time to put the political correctness on this issue aside. That’s why I’ve introduced an amendment to this year’s NDAA to direct the Department of Defense to assess the availability and usage of chaplains, houses of worship and other spiritual resources for members of the Armed Forces of all self-identified religious affiliations. We must focus on the spiritual fitness of our force to help them survive the emotional horror of war. Until we figure this out, we will continue to have our warriors struggle and it will be our fault for not addressing this important need.

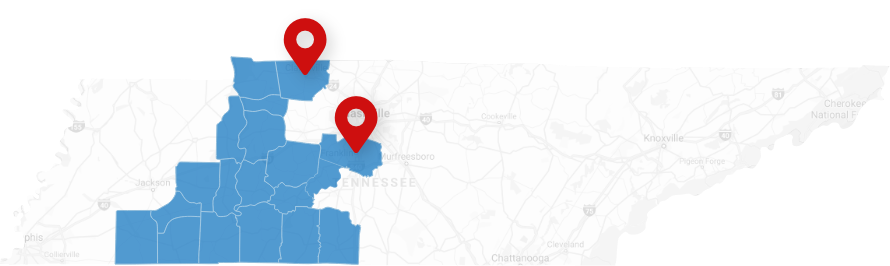

Representing the 7th District of Tennessee, U.S. Congressman Mark Green, M.D. is a graduate of West Point and combat veteran who served in Afghanistan and Iraq.